Eat to beat anxiety, depression and other mental problems

In April 2016, I attended an NSA symposium in Sydney where I heard a detailed presentation by Professor Felice Jacka entitled Diet and Mental Health: Results from the first randomised control trial to investigate the benefits of dietary improvement on mental health. Or ‘If I improve my diet, will my mental health improve?’

![]() This post has been sponsored by MLA.

This post has been sponsored by MLA.

If I improve my diet, will my mental health improve?

The answer is a resounding Yes! Even though it seems obvious (that your mood and general mental wellbeing will improve with a healthier quality diet), there has never been a definitive study to provide the evidence for this – until now. I listened eagerly to hear what Associate Professor Felice Jacka from Deakin University had to say on the topic.

Professor Jacka is well qualified to study diet and mental health problems, being the President of the International Society for Nutritional Psychiatry Research (ISNPR) and the Australian Alliance for the Prevention of Mental Disorders, as well as the author of many studies on diet and mental disorders from across the globe.

She presented details of a new ground-breaking trial from her team showing that a healthy, modified Mediterranean diet (nicknamed the ModiMed Diet) can reduce the likelihood of mental disorders.

Take-home points

Professor Jacka’s key points were:

Mental and substance use disorders are now the leading cause of disability globally (which means an inability to work including distress, loss of day-to-day functioning, poor relationships and social connections). So expect to see more in this space in the coming year.

- The two most common mental disorders (accounting for around 58 per cent of the disease burden) are depression and anxiety.

- Other less common conditions include schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, eating disorders (e.g. anorexia and bulimia), alcohol abuse disease and drug abuse disorders.

- Diet related mental health problems affect children too. Half of all mental disorders appear by the age of 14.

Past research

I found Jacka’s past research fascinating. As well as establishing that diet quality is related to mental disorders across the life course, she has found that the quality of people’s diet is related to the volume of their hippocampus in older age. The hippocampus is central to learning and memory across the lifespan.

While this has fitted neatly with all the animal data, scientists had not established this association in humans before. She also said that higher adherence to a Mediterranean Diet is associated with a reduced risk of depression. However, while the data from the population surveys had been very consistent, scientists have been lacking the clinical intervention data that can prove cause and effect - until now.

In this study

In this trial of 67 people (called the SMILES intervention and funded by the NH&MRC), participants were randomised to receive dietary counselling from an Accredited Practising Dietitian or an equivalent in social support counselling called controls. The participants both had 7 individual sessions that ran over 12 weeks in parallel groups over 2012-15.

All participants were required to be suffering from moderate-to-severe depression, have a poor diet quality, and to be on stable anti-depressant medication or psychotherapy, or no existing therapy.

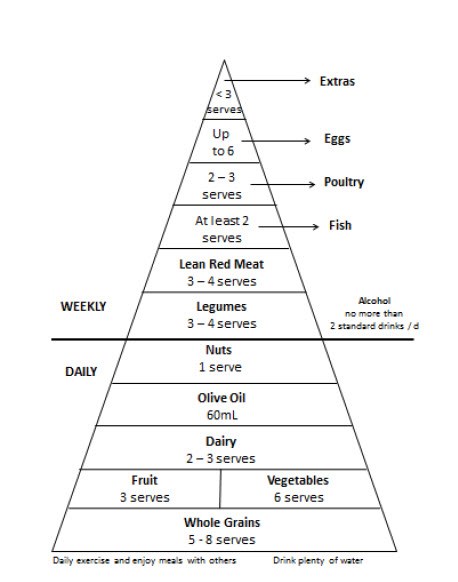

This ModiMedDiet Pyramid was created by dietitian and Ph D candidate Rachelle S Opie

Anyone with allergies, diet exclusions (vegetarianism/veganism) or aversions to foods was excluded from the study.

This SMILES trial was based on a diet intervention and used a modified Mediterranean Diet called the ModiMed Diet, designed by pH D student Rachelle Opie and Catherine Itsiopoulos (whose Mediterranean Diet book I reviewed here. ).

The intervention diet was primarily constructed using the Australian Dietary guidelines {National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC)}, the Dietary Guidelines for Adults in Greece {Ministry of Health and Welfare, 1999}, and scientific evidence from the emerging field of Nutritional Psychiatric Epidemiology.

Of note, the main modification was to recommend that participants consume moderate amounts of unprocessed lean red meat 3-4 times per week (think a palm-sized portion of red meat 3-4 times a week), consistent with the Australian dietary guidelines. This is because Jacka’s previous research had shown that red meat 3-4 serves a week was associated with a reduced likelihood of depression and anxiety disorders.

These researchers developed a ModiMed Diet score to measure adherence to their dietary plan.

Results

People in the dietary intervention had a reduction in their symptoms of depression, with 30 per cent achieving clinical remission compared to only 8 per cent in the control group.

What did the diet trial group do differently?

Daily - they increased their intake of whole grain cereals, fresh fruit, dairy and olive oil (not surprising for a Mediterranean Diet).

Weekly – they ate more pulses (lentils, chick peas) and fish, whilst substantially reducing their intake of discretionary items such as pizza, muffins and lollies

Yes they didn’t eat a perfect diet - but from where they started, the diet shifted to a much healthier one.

Note there were limitations to interpretation:

This was only a single-blind study, with a small sample size, and the mechanisms are still unclear. However there was a low dropout rate i.e. 94 per cent of the participants in the diet group went to completion as opposed to 72 per cent of those in the therapy group.

The bottom line

This is the first trial to show that a healthy diet (with more vegetables, whole grains, fresh fruit, dairy, olive oil, fish and pulses, and less discretionary items) can improve symptoms of major depressive disorder. In other words, eating better means fewer depressive symptoms and less time off work.

Given that there are no new drug treatments, and psycho-therapy improves any outcome by about 30 per cent, regardless of the type, looking at a healthy diet is another positive option for treatment.

Additional benefits from a healthy nutrient-dense diet are that it can improve co-morbid illness such as obesity (which often leads to diabetes) and heart disease. What’s more, it’s likely to be cost effective.

While these finding are hardly revolutionary, it’s good to have this confirmed by rigorous science that can stand up to scrutiny. It also supports the value of eating according to the Australian Dietary Guidelines